.jpg)

More than two in three children experience corporal – or violent – discipline at the hands of those meant to love them most: their caregivers. It’s a problem that affects children across the world, and a problem that Dr Cathy Ward, our latest End Violence Champion, has dedicated her life to solving.

As a high school teacher, she picked up on the vast inequities between her students in her home country of South Africa – and quickly, she realized that parenting, violence, and abuse had a huge impact on children’s social and educational well-being. As she pursued a PhD in clinical-community psychology in the United States, she explored these links further. Eventually, Dr Ward collaborated with a group of colleagues to launch Parenting for Lifelong Health, a suite of affordable parenting programmes aimed to prevent violence against children in low- and middle-income countries.

Today, Parenting for Lifelong Health programming has been implemented in 25 countries across the world, with trainings led by organisations including Clowns Without Borders South Africa, the Institute for Life Course Health Research at Stellenbosch University, and the Children’s Early Intervention Trust. A recent study found that this suite of programmes – which are available for four age groups – have averted 81,000 cases of child abuse. The End Violence Partnership spoke with Dr Ward about her experiences in the positive parenting space, and the impact that nurturing, violence-free environments can have on children’s lifelong well-being.

How did you become interested in violence prevention?

I was born in Cape Town in 1966. By the time I was an early adolescent, anti-apartheid activism was in full force, and I was living in a country that was very divided. I realized early on that there were many divides between the black and white populations of South Africa, something that became even more clear once I graduated from university and became a high school teacher.

Though I’d always wanted to be a clinical psychologist, becoming a teacher was one step in my process of getting there. Teaching, especially in the wake of South Africa’s integration of schools, opened my eyes to the differences in privilege between students – and the impact that privilege, inequality, and parenting could have on students’ academic performance and social wellbeing.

It was clear that children whose parents were very involved in their lives did better both in and out of the classroom.

It was clear that children whose parents were very involved in their lives did better both in and out of the classroom. There was such a difference between children with supportive parents and those without; those from more marginalized backgrounds were often exposed to violence in their homes and communities from an early age, but an involved parent could make all the difference.

I taught high school students for four years, and eventually, left South Africa to pursue my PhD in Clinical-Community Psychology at the University of South Carolina. Living in the southern United States, I was again made aware of the enduring legacy that lack of privilege, marginalization, and violence can cause. During my doctorate, I explored this concept further: by studying youth delinquency, I found that children’s exposure to violence could lead to that child perpetuating further violence in youth. My fear was that this kind of stuff does linger – and that to reduce violence, it was critical to reduce child maltreatment, too.

Later, I saw the same patterns as a psychologist. If you look at a child with a troubling trajectory, like someone who begins by stealing toys, then gets older and starts mugging, then turns to violent crime… it’s the kind of thing that we could have turned around early, if that child had more support at the beginning. Once you begin looking into youth violence, you very quickly need to begin looking into children’s earliest influences – and the type of parenting they were and are getting.

How did this realization give way to Parenting for Lifelong Health?

In 2009, I attended a World Health Organization meeting where they were promoting positive parenting practices and featuring organisations and individuals that had led evidence-based parenting programmes around the world. I started talking to a few of my colleagues in the space, and we decided we would try to adapt one particular programme, which was working to promote positive parenting in a high-income country, to a South African context.

At the same time, my colleague Lucie Cluver was researching the ways teenagers in HIV-affected families were being abused at much higher rates than teenagers in non-HIV-affected families. She was interested in developing a initiative to combat this abuse in South Africa. We wrote separate grant proposals, but the donor we were applying to saw the overlaps and asked if we would consider working together. We agreed and adapted our programmes – but in the process, realized that the existing initiatives were much too expensive for a country like South Africa. Because of that, we decided to devise one of our own. We reworked our grant proposal, sent it to the donor, and hoped for the best, but we didn’t get the money.

Even so, we weren’t daunted. The more we looked into the issue, the more we realized how big the need was, especially in low- and middle-income countries. It was very clear that if parents and caregivers in those countries were to be supported, the programme needed to be as low-cost as possible. Luckily, the World Health Organization had also picked up on this, and was interested in adapting evidence-based parenting programmes for low-resource settings. We joined forces with them, received some seed funding to implement a pilot project in South Africa, and began developing and testing the programme further. The project ended up working well, and that was the basis for what is today Parenting for Lifelong Health’s programme for young children.

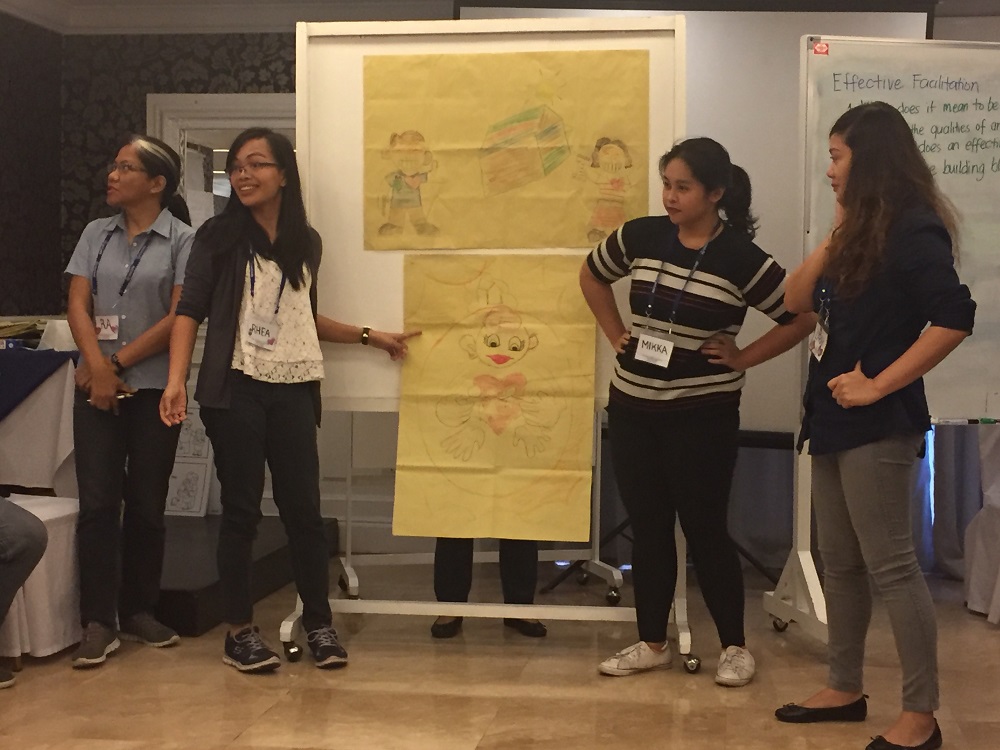

Partners in the Philippines implement a Parenting for Lifelong Health programme.

Partners in the Philippines implement a Parenting for Lifelong Health programme.

Today, we have four programmes, each focused on a different age range. There is PLH for parents and teens, which targets parents and children aged 10-17; PLH for parents of young children, which targets children aged 2-0; PLH for parents of toddlers, which targets children aged 1-5; and PLH for parents of infants, which targets mothers from conception to when their child is 6 months old.

The materials for each programme can be downloaded for free on the World Health Organization website in 15 languages, so anyone can access them. That being said, we do note that those implementing the programmes should be trained, as doing so does require fairly sophisticated group coordination skills. Clowns Without Borders South Africa (CWBSA) is the main partner that delivers that training, as they’ve been part of the whole thing since the very beginning. I really have to take my hat off to them, as they went from doing a few small trials in South Africa to receiving – and delivering – requests from all over the world.

How do Parenting for Lifelong Health’s programmes work?

Since the original studies, we’ve let the programme go free into the wild. Of course, the programmes will always be more effective if a partner – like CWBSA – trains and coaches the facilitators of the programme. So when USAID, for example, puts out a call for proposals for organisations to implement the Parenting for Lifelong Health package in a particular country, often, that cost will be embedded into the grant. There are a few different trainings to start the project, including a five-day intensive workshop on how to deliver the programme – the facilitator training; a three-day workshop for coaches and supervisors; and a five-day train-the-trainer workshop to equip trainers on designing and delivering additional trainings to PLH facilitators and peer coaches.

Right now, our programmes are being implemented in more than 25 countries, and sometimes, more than one partner is doing so within a country. In Zimbabwe, for example, both Catholic Relief Services and FHI360 are implementing the programme, and another partner – Plan International – is working with us on an adaptation of the teen programme to include a focus on reducing intimate partner violence. Every time partners in a new country utilize the package, however, they do need to adapt it to the local context, as the original PLH programme has idioms and examples from South Africa. Clowns can work with organisations to create those adaptations and come to us, the developers, if there are concerns, or deeper changes, that occur in the process.

So, we now have colleagues in the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, throughout Eastern Europe, South Africa, and more. We have a cadre of people working on PLH throughout the world, and that’s how it should be. Today, we’re actually working on making the programmes even easier to adapt and access through a text messaging version of the programme, which can be implemented through WhatsApp, Telegram, Viber or whatever digital platform is most popular in a specific country. And at the onset of COVID-19, we adapted some key aspects of the programme into a positive parenting package specifically for parenting during isolation. Today, that adapted package has reached 193.7 million people across the world.

It’s wonderful to me that people are using these programmes, loving them, and seeing the impact they’ve made. I’ve been enormously surprised by the worldwide – and rapid – up-take. It has been amazing. Terrifying, but amazing. And I’ve been so heartened by the effects: whenever the programme ends, so many parents say they want it to continue, and that it was a wonderful experience. Even the facilitators benefit; in our very first programme, I remember so many of them coming back after the first few days of the training saying that the tips and resources were helping them turn their family life around, even their relationships with their partners.

Partners in the Baltic Region implement a Parenting for Lifelong Health programme.

Partners in the Baltic Region implement a Parenting for Lifelong Health programme.

Why does parenting matter in the fight against violence?

All parents, no matter where you live or who you are, could use some help. Not everyone needs intensive help, and there are some contexts where problems – and violence – are more entrenched. But I think most parents find childcare at times bewildering, anxiety-provoking, or difficult – and would love to have some tips or support to help them out. And when parents are supported, children simply do better in school and in life.

When parents are supported, children simply do better in school and in life.

This is particularly true when it comes to violence. Just last week, a big paper was published with huge datasets showing that corporal punishment is bad for kids – and on top of that, it’s ineffective. If you get cross with a child and spank them, you stop them from what they are doing in the short term, but what you’ve really taught them is simple: don’t get caught. It doesn’t teach them what you want them to learn, and it doesn’t help them understand the value of positive behaviour. On top of that, if you control your own aggression, it also helps children learn to do the same – and in the inverse, when you exhibit aggression and violence, that serves as a model for children’s future behaviours. It’s not a stretch when I say it’s the gospel truth that positive parenting makes all of the difference.

All of that only gets more intense when children become older. Teens need to leave the home progressively and explore the outside world. If by the time children turn into teenagers, all they are thinking about is not getting caught, you cut off the avenue for children to come back to the parent when something bad actually happens. You cut that off if you don’t have a good child-parent relationship from the beginning.

I saw this very vividly when a colleague of mine asked me to review her research on men who were in maximum security prisons for serious violent crimes, like murder. She asked me to read over the document, and I did so on a flight from Johannesburg to Cape Town. By the time I got off the two-hour flight, I felt quite ill: Her research was an unremitting story of children who had been beaten and neglected from the very start. I couldn’t stop thinking about what would have happened if, early on, something had changed in the relationship between the parents and their children, who were now serving prison sentences.

Do you think we have a shot at ending violence against children for good?

Yes, I do think that we do. I think almost every parent would be grateful for parenting advice, and if you frame it in a positive way – not saying, for example, just don’t hit your child – that can be picked up and accepted. After years of doing this programme, I haven’t heard a single parent say, after going through the programme, that they still need to hit their child. Because of that, I think we have a good shot at ending violence through parenting.