Mobile compatibility and on-the-go betting continues to set the standard at the best offshore sportsbooks, making them a top choice for US sports bettors seeking reliability and performance in 2025.

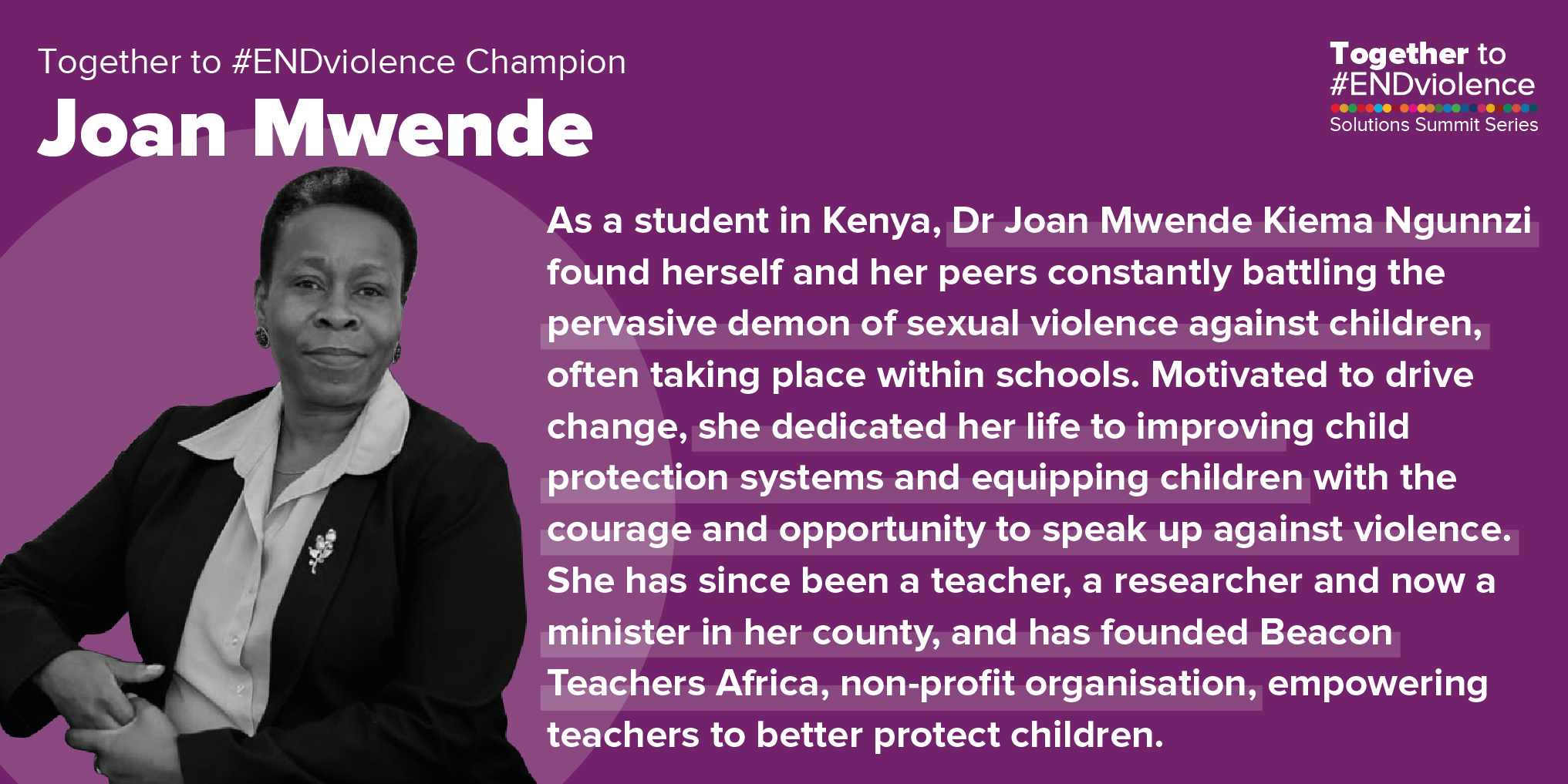

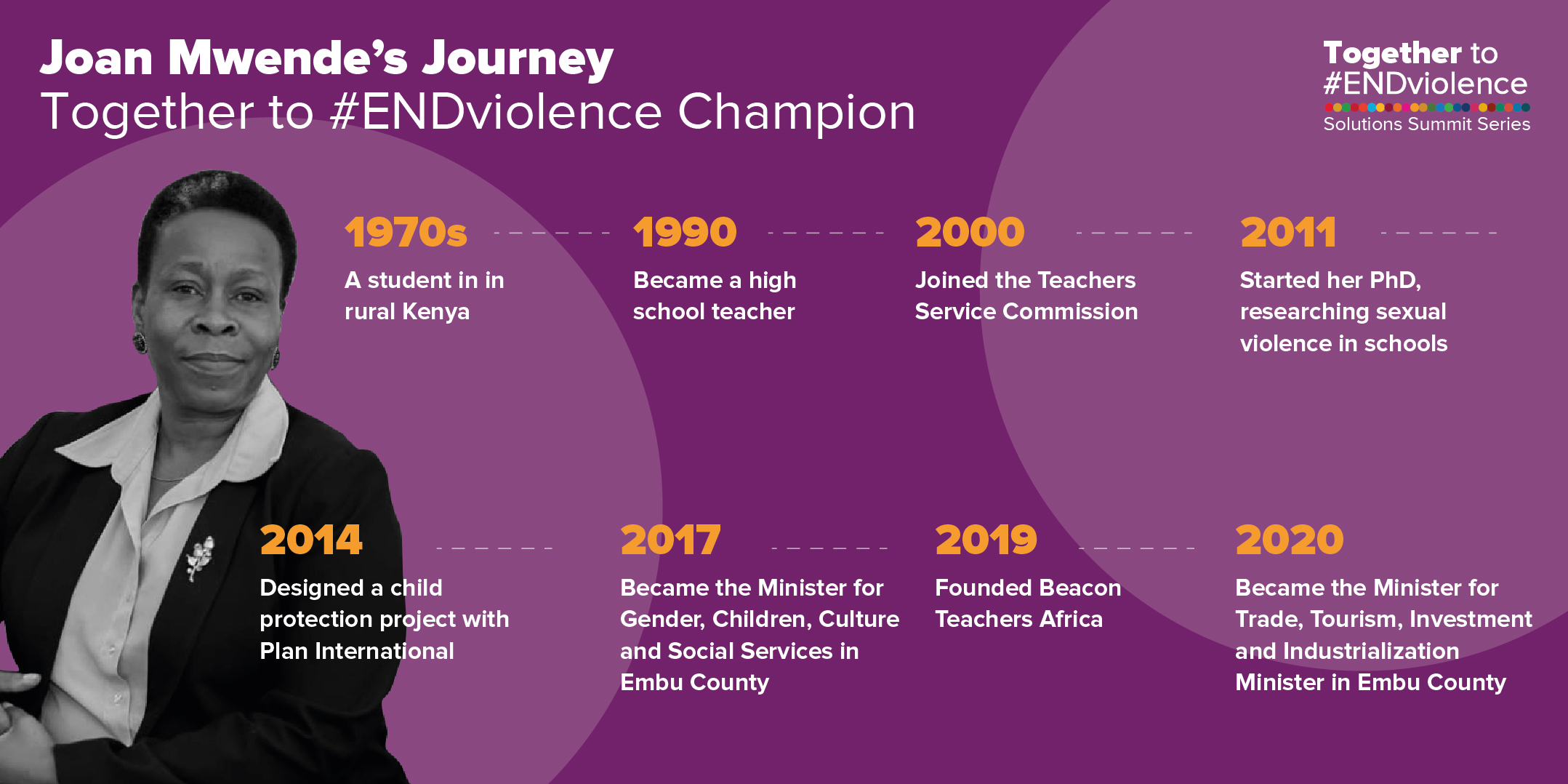

As a young girl growing up in a rural village in Eastern Kenya, Dr Joan Mwende Kiema Ngunnzi found herself constantly facing, and battling, a grave demon – pervasive sexual violence against children. And a lot of times, this violence was happening within schools – often at the hands of teachers themselves. A young Dr Ngunnzi, who fought off multiple attempts of sexual assault, credits her safety to one strength: the courage to speak up. And she made it her mission to equip school children across Africa with the same courage to break the silence.Through her teaching, research and government work, she realised what the children needed was empowered educators who are willing to listen and able to help. Since then, she has spearheaded child protection in the government of her county. She went on to hold two ministerial posts in her county government, and founded Beacon Teachers Africa, a non-profit organisation empowering school teachers with the tools and training needed to help protect children against violence, and foster positive and inspiring learning environments.

She shared her story with End Violence.

PART 1: Learning and teaching in Kenya

Dr Joan Mwende Kiema Ngunnzi is the Trade, Tourism, Investment and Industrialization Minister and Former Minister for Gender, Children, Culture and Social Services in Embu County, a county in the eastern region of Kenya. But her passion is in child protection – with which she has a long history.

Her passion to better the lives of children grew out of her own experiences as a child growing up in Kenya. Dr Ngunnzi faced and witnessed multiple instances of attempted sexual abuse and defilement as a child and young student within her community, and within its schools. She describes:

“In the early 70s, school wasn’t what it is today. We didn’t have the kind of policies that we have, the training of teachers that we have today. A number of times I heard children talking in low tones about sexual violence. It got to the point where even the boys in lower primary school – age 9, age 10 – also started to violate girls. That made me very scared and I kept on wondering why no one was doing anything about it. Every time a girl was defiled, a boy would be talking, laughing at them. I noticed, slowly by slowly, most of the girls would drop out – because of stigma, embarrassment…

I was 9 or 10. The teacher sent us to the river to draw water. I was carrying a five-liter jerry can, struggling with it. Somewhere in between, [a] boy dragged me and tried to defile me. We started to struggle, and because the place we were passing was bushy – tall elephant grass – in the process, I fell. I sustained deep cuts on my thighs. Eventually he left me, we went back to school, and I never reported to anyone – there wasn’t a place to report.

I never told any of my classmates, I never told my teachers, I never told my mother. The scars are still there to remind me of that day. At least for me, there were just those scars on my thighs. But I kept thinking, suppose that boy had succeeded? What would I be like? what would life be like?”

Not much later, as a teenager, Dr Ngunnzi faced attempts of abuse from those meant to guide and protect children – the teachers. Through her school life, multiple different teachers, all of them males, made direct attempts at sexual assault.

“From primary, I went to secondary school, and found the same thing: [this time it was] abusive teachers. At that time, a teacher tried to defile me during a Sunday Service. I was a school prefect on duty that week. He said go to the laboratory and close the curtains for me. I’ve forgotten to do it. So, I ran – I zoomed out of the Sunday Service and ran to the laboratory.

He came in and tried to defile me, but I fought with him so hard. He struggled, until the point I said I am going to scream so the whole school will be here to witness this. That was when he let me go. I realised: maybe if I hadn’t done that, if I hadn’t threatened him in that manner, he would have defiled me.”

Dr Ngunnzi faced the same thing again, with three other teachers, in high school all the way to university. Finding themselves alone with a student, male teachers made confident attempts at assault towards a young girl. Dr Ngunnzi, luckily, managed to fight off the attempt at abuse.

“Eventually, I managed to fight [them] off – but still look, I didn’t tell anyone. I didn’t speak of them until last year, when I was interviewed by our local television station. All those years, and I kept on wondering. Are other students going through this? Are they facing what I’m facing? I started to quietly investigate during my school days.

I realised those teachers were doing that because they were succeeding with other students, and all the other students were embarrassed to talk about it. There weren’t systems within the school to deal with this, to bring a case against a teacher. Teachers were like demi-gods. The school management wouldn’t listen. We had never heard of anyone coming to challenge a teacher.

It’s a lot of rot. Systemic rot that requires radical surgery. The fact that there is gender-based violence in these institutions!”

Through all this, Dr Ngunnzi started to realise that there was no help, no systems in place for children to address sexual abuse and violence. She credits her courage as the thing that helped her fight-off the abuse – making her speak up against the silence.

“Looking at all those things, at least for me, I had some self-confidence to deal with the characters who were trying to offend me. I had the boldness to say do what you want, I will not comply. I had the confidence that even if the worst came to the worst, I would not bend. But it’s not easy. One of my friends says , you’re such a risk-taker – I wouldn’t have the courage to do that. If I wasn’t able to fight back, if I wasn’t equipped, if I wasn’t strong enough to stand and say no, in my high school I would have been multiply defiled, this is what kept me saying even if no one else will, I will do something.”

Influenced by her experiences and what she saw around her, Joan decided to have a career as a teacher. She wanted to reform things and play her part in changing the lives of children in Kenya. Her first teaching experience was at a boy’s school, where she realised the prevalent problem of corporal punishment.

“When I started teaching high school, my first teaching station was in a boy’s school. At that particular point, cases of sexual violence against boys were not many. I didn’t know of any at that time. But corporal punishment was there – where teachers were beating the students senseless.

But barely one and half months down the line, I realised this doesn’t work. I would go back to my house in the evening feeling so bad. The next day, having to face the students you beat yesterday – it made me feel embarrassed. Every time I beat a student, I felt like I had broken a code. Like I had a covenant with them and now I had broken it. After my first month of teaching, I stopped caning students. I made up my mind to start speaking to them, start negotiating, asking them: why did you do what you did? And how do you think I feel about it? I feel uncomfortable that we’re having that conversation, and we could spend the time learning.

I was happier as a teacher. But I wasn’t able to convince my colleagues.”

Soon after, she began teaching at a girl’s school. This began her journey of speaking to young girls, creating safe spaces and empowering them in the face of violence.

“I was so excited. I began to speak to girls, to ask them how is life, how do you feel? In the school timetable, there was no provision for those types of discussions. But I made it my duty – when I had class before break, or my last class before lunch, or the last class of the day – I would say, can we spend 5 minutes talking about ourselves. I realised that the girls had so many things they wanted to share.

From there, the rest is history. I enjoyed teaching because opening that space gave my students a change to debrief, to clarify issues they were grappling with. It also gave my students a chance to build their confidence and learn from someone who had experience. To this day, my students still call me and say, We treasure those times, those moments.”

If you connect with a child, even the poorest child can learn… Unless you connect, you’re not teaching.

This is also where she realised the role, responsibility and power that educators have in ending violence against children and shaping more secure environments for them. She started to encourage more teachers to have chats or ‘open forums’, as she called them, with the students.

“When I became a teacher at the age of 24, my purpose was to speak to girls. Guidance and counseling was minimal in the schools. When it comes to dealing with issues as difficult as sexual violence, it takes passion, because it zaps all your emotional energy – it taps you to the bone, to the marrow. And you can’t sustain unless you have the passion. A paid worker might try, but it will be very easy to quit.

In my last teaching station, which was another girls’ school, I managed to get the teachers to come to my sessions. I used to call them open forums. A few other teachers started to join in, and with time, they began to copy and paste the same with their students.

There’s also something I learned. Students want to talk to someone who they can trust, someone who can give them a sense of belonging, of significance, not just because you’re a teacher counsellor.

Here in Kenya, one of the issues that troubles us is that there are a large number of teachers trained as counsellors, but students don’t confide in them or go to them for help because they don’t feel a sense of trust, confidence or significance. They don’t have a connection with those teachers. I began to realise that one of the things that the counseling school should do, especially for teachers, is to have them get the students to connect with them, so you can build a relationship, trust, confidence. So when the student is speaking to them, they think: I am speaking to someone that recognises me as a human being with emotions, heart, all that.

Discussions around sex and sexuality are not common in Kenya. Its taboo. But I realised, when I opened up to the girls and told them, imagine what happened to me in high school. That helped to break the ground, and they began to think – ‘oh, we are not alone’. I would give them ideas on how to deal with this, knowing that there was not proper protocol with managing these things. I gave my students some tips, survival skills.”

Dr Ngunnzi explained how many students faced violence in various settings of their lives, how it remains hidden and how it affects every aspect of their learning and development. Culture and societal norms also enable abuse, and keep it hidden when it happens.

“At my last school, one of the students who was “unlearning” as we call it – she never learned what she was supposed to learn from early childhood to Form 3 (age 17). She happened to come to my school at Form 3, and when I interacted with her, I realised she hadn’t been learning anything. When I followed up with her, I realised she had come from a background that was very violent. Her father was very violent, and she had a physical disability. A lot of the pain she had been suffering was from the violence of the father onto the mother. I had to help her unlearn that violence somehow, open up.

It took me just two years to teach that girl what she should have learned from primary to Form 4. Why? Because we connected, because I gave her a sense of belonging and significance. I raised her self esteem and made her feel very important. To this day, she says you are the only person in this life whoever made me feel important. Because of that connection, learning for her became easier. In just two years, she learned what she was supposed to learn and passed to university. Today she’s a graduate and works with Kenya Graduate Authority.

This is what makes me so passionate about teaching children to self-protect and build a community, population of champions for children. If you connect with a child, even the poorest child can learn… Unless you connect, you’re not teaching.”

Teaching children fuelled Dr Ngunnzi’s curiosity and passion to better the lives of children even further, to better protect them. Feeling compelled to drive change, she began her journey of working to transform teaching systems in Kenya. Read part two to know more about her efforts.

PART 2: Transforming schools, protecting children

Dr Joan Mwende Kiema Ngunnzi has spearheaded child protection in her country, Kenya. Fuelled by her own experiences of having witnessed and faced pervasive sexual violence against children in schools growing up, she has worked to reform teaching systems.

In Part 1, Dr Ngunnzi shared with us her experiences as a school girl in rural Kenya, how that motivated her to teach and help children be safer in schools, and what she learned as a young educator. Through teaching, Dr Ngunnzi was motivated to bring lasting transformation in schools. Here is her journey of driving systemic change for children.

….

Over 10 years of teaching children fuelled Dr Ngunnzi’s curiosity and passion to better the lives of children even further, to better protect them. She started to learn more about the abuse and violence that children were facing in schools in her country. She felt compelled to learn more, do more and drive more change.

“Back in 2004, I was just lazing around the internet, I saw a story about a particular teacher. This teacher was complaining that he wanted to be transferred because the parents were bringing girls to the teachers’ houses, selling girls to them! That caught my eye. I began to search the internet for violence against children, sexual iolence.

Then in 2009, I had an opportunity with an organisation called CRU. They said, can you help us do an examination? I was alble to peruse through all the Kenyan Teachers’ Commission’s policies, acts, and structures, that were at that point in place to prevent and respond to sexual violence in schools. But what bothered me most about the srurvey was finding that the systems were so fluid, that a teacher could get away with sexual violence and keep teaching in the same school.

There were so many cases that had been reported but had not been concluded. I began to dig deeper, I searched every space. Old spaces from 2003 to 2007. The majority of the cases had never been concluded , which meant the teachers were still in schools. I realised that less than 10% of them had been prosecuted. Why? According to the commission, there was a boundary. Once the teacher was dismissed, that was the issue of the parent, of the victim. I raised these issues in a stakeholders’ forum – with 200 stakeholders. I watched the way they reacted, they were baffled at what was happening. I saw many of them weeping. From that survey, 633 teachers had been discmissed for violence against children, sexual violence. But nobody had a count of the number of children they had been defiled. But from the survey ,I realized a teacher could have defiled 10, 20, children.

In my research, I came across a student who had abused children for 30 years. One teacher, one school, abusing children every other day! Within that period, nobody has the count of the number of children who had been abused through those schools. Everyone agreed that sexual violence was pervasive, but everyone sounded so helpless.”

After teaching for 10 years, Dr Ngunnzi went on to work for the Teachers’ Commission in Kenya, working towards systemic transformation in teaching systems. She then also pursed her PhD, and did her thesis on the crisis of sexual abuse of school children by teachers in Kenya, focusing on cases in Makwane in the eastern region. Through her research, Dr Ngunnzi realised that there were missing links in protecting children at schools – teachers needed to be brought together and trained to protect children from harm, sometimes coming from fellow teachers. She used her experience and research to drive solutions.

“From this research, it became apparent to me that without effective teacher engagement, there would be no hope for the mitigation of sexual abuse of school children by teachers. In 2014, I had the opportunity to design a child protection project with Plan International ( focused to end violence against children), which was funded by the European Union. I had the opportunity to plough in my research ideas into the project and craft out the next step , the Beacon Teachers Movement.”

In 2019, she founded Beacon Teachers Africa – a pan-African, non-profit organisation, empowering teachers by supporting their professional development, advocating for an enabling environment for children and building their capacity in child protection. This effort is part of Beacon Teachers Movement which was a pilot project of the Teachers Service Commission supported by the European Union under their programmes to End Violence Against Children.

“The reason I founded Beacon Teachers Africa was to educate the community on the crisis of sexual abuse of school children by teachers in Kenya and to make sure sure children have an anchor so they have someone they can fall back to, to educate them, train them, nurture them, and build the stability to survive. So the children can have someone report if there is a threat, so they can have a place to run to. I wanted to raise a population of teachers with the stability, passion to stick with children.”

I wanted to raise a population of teachers with the stability, passion to stick with children.

Beacon Teachers are largely teachers under the Kenyan Teachers Service Commission. The organisation has 3,000 registered educators, working with a larger network of over 50,000 teachers across Africa. Through this network, the non-profit is working to support teachers to embrace positive discipline approaches, help them protect children against violence, grow professionally and create a positive and inspiring learning environment for all children.

“At Beacon Teachers Africa, all the members stick out their necks for children. Beacon teachers advocate the rights of children. Most importantly, we do everything to prevent violence and respond to violence against children.

Beacon Teachers support children to press charges not just against teachers but any other person including their relatives and other community members. Many children have complained about incest, sexual abuse in the home, and many of our teachers have taken these family members to court.

For example, we are currently handling a case of an 8 year old girl in Embu court who was sodomised by her father. Within the Beacon’s induction, we take teachers through the policy and legislative provisions for protecting children which include Article 53 of the constitution of Kenya [which states children’s rights be protected from abuse], the Sexual Offences Act, CRC, the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child.

Beacon Teachers also work in collaboration with state and non-state actors on the ground to leverage skills and other resources. We have an annual Beacons Forum that brings together Beacon Leads from across the 47 counties where we brainstorm on emerging issues. Our strongest point is that we leave no stone unturned. We network with the police, collaborate with Plan International, World Vision, media stations.

Beacon Teachers Africa also trains the teachers to change existing negative practices within schools, and to make sure that they are not causing any harm to children.

“During my research, I established that teachers who are violent are also more likely to defile children. Why? Because children fear. And when they fear, they will easily comply. So, we are advocating for non-punitive approaches of discipline, training teachers. One of the things we have found very valuable is that when the teacher is able to bond with a child, when the teacher has love for them.

Our teachers have committed, there is no point teaching a child that is hurting. So we deal with the hurt, and then we can teach the child. How can you teach a bleeding child? It’s useless.

We have been raising this with education officials and the department. There is no point wasting all these resources – desks, tables, etc – it doesn’t matter how much you put into the school. Until you deal with abuse of children, there’s no education.”

Dr Ngunnzi shed light on the challenges that BETA faces. She says there is much to be done still in changing mindsets and in improving systems.

“Defilement in our country and in the schools is so alive that it will take a multi-pronged approach, multiple partners, it will take a rethinking of those strategies. Here in kenya, parents [and teachers] may be violent because of culture, a culture that tells you you must beat your child or else you will look weak. So part of it is education, educating all teachers in kenya.

At BETA, one of the issues we are grappling with right now is that the systems are still not flowing. They are not doing what they should. A lot of times, teachers have been left with the survivors in their hands and they have to struggle to figure out what to do. When I dealt with the case of a 30-year defiler, eventually, I was left in my hands with two boys. I didn’t know what to do with them, and I tried every place to find help.

So, we are training training teachers on the regulations, on the law, provisions of the law, sexual offences act, children’s act, CRC, we teach them about child participation, train them on positive discipline also.”

Dr Ngunnzi is working to address these challenges and continue to drive more transformational change in Kenya. Her focus and passion remains in ensuring the safety of all children.

“If we have saved one child, we can save a generation,” she says.

ABOUT END VIOLENCE CHAMPIONS

As part of the Together to #ENDviolence global campaign, we are celebrating these individuals and the change they are helping to create. Through Q&A-style interviews, you will learn from practitioners, activists, researchers, policymakers and children about their successes, their challenges, and what they think is needed to end violence for good. Every month, we will feature someone working on this challenge from a different part of the world, shedding light on their impact and the efforts of their affiliated organisation, company or institution.

Do you know someone who should be featured as an End Violence Champion? Nominate them here!